Remembering Dad

1904 ~ 1980

| What follows here is a journey through the golden meadows of my memory, such as it is - a look at my Dad in tales and anecdotes and memory traces, in no specific order - word images that flesh out and define the man who defines me so thoroughly... |

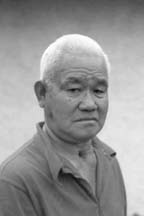

Silence. Deep silence, and a firmly set lip. Large brown eyes with a whisper of darkness within them. He was a man of the earth - he had dirt under his fingernails, and mud on his work boots, even when he cleaned up. You felt it from the time he clasped your hand in a firm handshake, for his large hands were hard and callused from an age of hard labor. Yet, he was able to tie the most intricate of knots with the slimmest of fishing leader. He mostly wore khakis and a heavy cotton shirt in the fall and winter time, with an orange zippered hooded sweatshirt for warmth, and a weathered and crumpled sweat-stained hat. In the spring and summer, khakis and a white T-shirt. He was big-boned for a Japanese, though in stature he wasn't tall by any measure - still, he was taller than I was to become on my American diet...

Silent with an outer calm, but with an intense inner world the verge between the deep of mystery and delicate almond blossoms in spring - that was Dad. In so many ways an enigma, yet for me in hindsight, somewhat of an open book. A man of few words, it was clear his take on things of import. Extremely courteous, yet not obsequious, uneducated, but knowing in matters of living, tough in the face of challenges, yet tender in his relationships with his children - conscientious, steadfast, and true..

It was a hard life growing up on the farm - not bone-crushing hard, or so severe as to destroy the spirit, but hard enough to "build character," as they say. Days on the farm were long - sometimes you rose before sunrise, worked through twilight and into the night, and in between you went to school. And, there were always chores. But there were softer times as well - time for family. When we were younger we piled into the car and took off on Sunday drives - something long lost in the misty past. Sometimes we visited family or relatives, sometimes friends. Sometimes we just drove here and there - it was like being in a time capsule just with family. The first car I recall was a powder blue Plymouth - four doors, big and boxy, a running board, with that sailing ship hood ornament. The back doors, as I recall, opened "the wrong way." Dad always drove - that was the way things were then. During the winter we still went driving, though we kept the windows closed to keep us warm and dry. In the late spring and into summer, when the weather warmed and the harvest didn't conflict, we drove with the windows down - that was our "air conditioning."...

Dad went to school in California when he first arrived from Hiroshima, Japan, but attended only for a short time. He left school at an early age to go to work to put his younger and favored brother through school. Because his schooling was rather short, he didn't learn English well, and for the rest of his life spoke in what we quaintly called "broken English." Those who didn't know him well initially had a tough time understanding him. As we were growing up this was a major source of embarrassment for us. As far as family values and moral standards went, though, he was very clear....

Family wasn't just important, it was everything - it was where you did things with and for the family. The first time I chose not to go with friends to hang out at Lake Merced on a Saturday, and instead stayed home to work, was a proud day for Dad. We all had our chores, and the expectation was that you carried them out. For the most part we all did, because family was important to us as well. We were a close-knit family, and there is no doubt that was partly the result of being one of only two Japanese-American families in the community after WWII. It's pretty amazing how a feeling for family develops - it's a compilation of a thousand factors, some major and obvious, others so subtle you have no idea they're working on you. Mom and Dad set the tone at home, and guided us as we made our way in the world outside the home. Then, too, there were so many adults in the community who knew Mom and Dad who made up a much larger "extended family," that if ever we stepped out of line, word reached home well before we did, and we had the privilege of explaining ourselves with our first step inside the front door...

As I have said, Dad wasn't much for talking. This in part was due to a personality type that encompassed introversion and deep thought, compromised by English being his second language. When it came to explanation or conversation, he was pretty much at a loss for words. I recall one freezing cold day when he was teaching me how to prune fruit trees - we were standing some 10 feet above the ground atop a platform attached over our Ford tractor. There were iron guard-railings to prevent our falling off, with dual controls for the clutch, brake, accelerator, and steering mechanism permitting us to "drive" the moving platform from tree to tree without having to descend to do that. Dad pointed to a place on a branch and said to "cut here." I asked, "Why there?" His face stoic and giving no clue as to what he was thinking, he paused searching for words to explain - "That's where you cut." Pause: I said, "I don't understand why you cut it there." He continued on: "Cut here." Dad was uncomfortable - I was uncomfortable, and I didn't ask any further. Needless to say, I didn't really learn the art that day, or ever after. In later years in a moment of inspiration it occurred to me that it had to do with thinning enough buds from along the branch to insure there wasn't a surfeit of fruit at harvest time. Too much fruit on a single branch, and they'd be small and the sugar content overall less. At the time, I didn't understand any of this. In hind-sight, I felt for Dad as he tried to explain to me an art he had mastered, but couldn't describe.

Dad was an artist of sorts, with an appreciation for the aesthetic - not that he would have said this. He was a farmer. His family and the families in this line back through time were all farmers. Somewhere in the distant past, though, at some generational juncture, a male of the samurai warrior class entered this line. The story goes that the Nagai family at that point had only daughters, and in all the extended family there were only girls - the Nagai line was going to end with that generation. As happens in such cases, the family arranged a marriage with a young man of another family, the Sagawas of a warrior class, and the young man took on the Nagai family name. Thus, the Nagai line continued in time.

Here's where the artist comes in - while most farmers in post WWII central California maintained a "co-existence" relationship with weeds, meaning they "let them go," Dad aggressively sought to eliminate them. This was expensive and time-consuming, but it was something he did. This meant we did. Weeds do two things not good for crops: 1) they take water and nutrients from the soil that should go to the crops; and 2) they detract from the aesthetic look of the orchards and vineyards. The first is scientifically based, at least in theory, and I credit Dad for this perspective. The latter was more impressive to me as a closet-artist growing up. A clean orchard was pretty impressive. Of course, the down side was that I spent many an hour hoeing weeds by hand, and hours on the tractor dragging a disc or spring-toothed harrow taking it out on all those weeds. We did have a clean ranch as a result.

Dad was an equalitarian at heart - traditionally, the Japanese male is the master of the house, and his wife takes her "rightful place" several paces behind. Not so with Dad. He and Mom were equals, and shared everything in their lives - they worked side-by-side throughout the year. In the fall and winter they pruned the fruit trees and grape vines. They each drove the tractor and disc throughout the year, and in the summer brought in the harvest. And, when the ditch buck said the water was ours, regardless of the time of day or night, they went out to "chase water." Together they built our first home - Dad and Jiichan, Japanese for grandfather, poured the foundation, raised the framing and walls, affixed the roof, and did the plumbing, while Mom did all the electrical wiring. I don't know how Mom learned about electricity, but the point being it all worked and passed code. Mom also did all the cooking, so had that "job" on top of being a "gentle-woman farmer." Dad helped out in the kitchen, maintained the vegetable garden, mowed the lawn, helped with the laundry, kept the chickens, and made sure the family car was maintained, as well as all the other farm equipment. While Dad wasn't an overtly emotional or demonstrative person, those occasions in the kitchen gave light to his manner of saying to Mom, "I love you."

Dad had this incredible internal alarm clock that modulated his life as a farmer. He did have an alarm clock on the night stand, but never used it to my knowledge. He rose unaided when he needed to, regardless of the time of day or night, and went off to work - I never figured out how he did that.

One Thanksgiving after I'd been married a couple of years, the whole family gathered at the old homestead for the holidays. Gene and Cindy were there, David was up from college, Barbara and I were in from Berkeley, and Janet and Hank came up from Fresno. Crowded, but cozy. Very quickly a pinochle game started in the living room, and a strange thing happened - no money exchanged hands, as this was family and for fun, but the game took on a monster quality all its own, devouring time as had never happened with any event in the family ever before. That first day we must have played 8-9 hours straight. The intensity of the game was palpable. The next day, it resumed for another 13 hour marathon, and we barely stopped for meals. Dad wasn't pleased, and finally called us on it - we, none of us, had been helping out in the kitchen, neither in preparations nor in cleanup. Chagrinned, we pitched in to help Mom out - late, but still...

I'm a lot like my Dad - an introvert with a world of things going on inside, though you'd hardly know it to look at me - basically shy, stressed if called upon to speak in public, dislike for large crowds, especially of people I don't know or know only a little, hopelessly sentimental, liking of simpler things, and family. I love family. Dad loved family.

Dad was a nominal Buddhist, but wasn't a practicing participant when he came to this country. He nevertheless held strong moral values that had to do with right and wrong, that came out of a family and culture of doing what's right, honoring your parents and elders and those to whom respect is due by office, position, or merit; obeying the law, doing right by family, giving full measure in everything, and especially working hard, giving service, appreciating your life and the benefits you receive, and giving back. The power of family. When I took a stand as a conscientious objector in graduate school, a time when the Vietnam war was just "heating up" but before it became somewhat official, this was a very difficult time for Mom and Dad. Here I was, their first-born son, and I was doing something that in their eyes and life experiences during WWII resulted in people going to prison. To the Japanese, to break the law, to defy authority or show disrespect, especially if against the social mores of society, meant the loss of face, the dishonoring of the family name, bringing shame upon the family. Major taboo, this. I give a lot of credit to Mom and Dad, for in spite of such conditioning and emotions that ran so deep, they stood by me during this trying time.

Irrigating orchards and vineyards is one of the most solitary tasks on the farm. Dad often woke up in the middle of the night to accept the water, and worked through the day till twilight with only brief stops for meals before he "set the water" for the night. This meant opening the valve of the standpipe to allow just a trickle to run, and if set just right that trickle reached the end of that row by morning. We set water for the night throughout the orchard and vineyard. In the morning Dad would open the valve and route the water into the next row. When I worked with Dad irrigating we rarely spoke, in part because we often were working different sections of the orchard or vineyard, but also because we both were inner silent types. We sometimes didn't see each other until lunchtime when we sat down for the mid-day meal. Pretty much uneventful, this task, but it required a level of vigilance in case one of the furrows or levies broke sending water in the wrong flooding and uncontrolled direction. Once there was a break and flooding began, it involved shoveling a whole lot of dirt to fill in the break in the levy to bring the flooding under control. Did I say solitary? For an introvert these were prime times, and I spent the time deep in that wonder-full world of the inner while "chasing water" in the outer realm. I loved the time; Dad just took it in stride.

People can change. I'm not absolutely convinced of this, and being somewhat of a cynic I hesitate to say it, but it seems to happen enough that I'll allow it said. When I asked Barbara to marry me, we knew we were going to encounter some difficulties, not the least of which was with our own families. Inter-racial marriages weren't all that common in the early "60s." When I told Mom that I had proposed to Barbara, I mentioned in conversation that she was Caucasian. There was a pregnant pause - Mom: "I had hoped you would marry a Japanese girl..." Ouch. Barbara's Mother's response was similar: "I had hoped you'd marry an American..." Barbara's response: "Mother, he IS an American." Well, so much for smooth beginnings in marriage. However, with the birth of our firstborn, Paul, you would have thought we had enjoyed the full support of parents from the start. Paul's innocent cute face, his big brown eyes and long eyelashes, shock of thick dark hair, that mixture that is expressed so eloquently in the face of mixed-race children, touched something very deep in the grandparents, and they were summarily won over. Whatever residual racism that existed on both accounts, melted away on seeing the alert and shining face of a grandson. Being a grandparent now myself, I fully understand how that works.

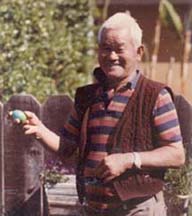

In 1963 I earned my Masters in Social Welfare degree from the Graduate School of Social Work at the University of California in Berkeley. Mom and Dad came up for the ceremonies held in the U.C. football stadium on the Cal campus. Before the ceremonies, Dad stood in front of our tiny basement apartment on Wheeler Street and had his picture taken in my mortarboard, and master's gown and hood. He was so proud - my graduate degree was the highest anyone in the family had achieved...

In 1948 President Harry Truman signed into law the Japanese-American Evacuation Claims Act, providing at least a token reimbursement to those incarcerated during the war for losses in income and property. Mom and Dad received an amount of $5,000 for their claim. Mom's comment on receiving this amount: "It just barely covered the cost of a new pickup truck." The disappointment was always in her voice when she spoke of it, later to be replaced with resigned cynicism - "Shikata ga-nai..." - "There's nothing you can do about it." Dad I think was just glad to get anything for the family's losses..

Discipline: Here's the thing - neither Mom nor Dad ever laid a hand on any of us kids - they didn't have to. With a raised eyebrow, that tone in the voice, a certain look or a choice word, and we fell right into line. These were things that "stung" more than a ruler on the backside or the back of the hand to the head. They were more than effective in molding our behavior. The downside, it instilled guilt as a motivator - the words, "You should know better...!" still ring in my ears...

Trust: from very early on Dad allowed me to drive all the various farm equipment. This included an ancient Case tractor that required that I stand on the clutch pedal to operate it in conjunction with the heavy gear shift because of my slight weight and stature, a Ford tractor, and later a larger Ford-Ferguson, and a Dodge military personnel carrier from WWII, converted with a "fifth wheel" and a semi-trailer. My first driving lesson was with the converted personnel carrier when I must have been 8 years old, and still couldn't reach any of the pedals. Dad sat me on his lap while he operated the clutch, brake, and gas pedal and I operated the steering wheel. When I grew enough, I drove all the tractors and tractor-trailer combinations, hauling fruit, grapes, and nuts out of the fields, driving crops in to the Atwater Fruit Exchange that bought our produce, and on lonely Saturday mornings drove the Ford with a spring-tooth harrow behind to till the soil. Much of this before I had my driver's license, except the part about driving in to the Fruit Exchange as that was "into town." Dad gave me considerable responsibility for handling what were actually very large and dangerous farm equipment. He was serious in his instructions on how to work them, and of the need for safety at all times - the most important thing I felt in all of this was his trust in me with such responsibility.

In November of 1922 the U.S. Supreme Court confirmed an earlier legislative act of congress restricting acquired citizenship to "free white people." This decision ruled that Japanese aliens specifically could not become naturalized citizens. As a follow-up to vigorous agitation by western states, congress enacted the Japanese Exclusion Bill preventing Japanese immigration to the United States. In 1952 the U.S. Congress, over President Harry Truman's veto, passed the Walter-McCarran Act, reversing these laws thus allowing Japanese aliens to become naturalized citizens. This also reversed provisions of the 1913 California Alien Land Law that prohibited aliens, in this case Asians, and specifically Japanese, ineligible for citizenship from owning property in the state. This was why the family farm was in the name of my Mom, who was a citizen by birth of the U.S. That year, 1952, Dad was in the first "class of '52'" of Japanese aliens in Merced County to become naturalized Americans under the new law - a proud day for Dad, and for family and friends...

As Mom and Dad approached retirement age, Dad had this really crazy idea - to sell the Nagai property, buy a mobile home, and pick up and just tour the country. There were so many places Dad had not seen of the country of his heart, that he dreamed of this for years. The way it played out in his mind was that they would travel as far as interest took them, find a place to park their RV, and stay a spell exploring the locale. With no other restriction than time on their hands, to see as much of this great land as they could before they died. Then, when they ran out of interesting things to see or visit, or when their appetite was whetted and they were "full," they would return their roving home to where they had spent the better part of their married lives together, and settle in to full-time retirement. They would see the country from north to south, from west to east, and in the process match their Mother Country with the dream in their hearts. Well, at least that's what Dad would have loved to do. Dad's dream died in stillbirth though, for Mom, in whose name the farm was officially registered, was too security conscious, too anxious about their retirement, that to do other than "hold onto the land" would have been folly. With the land, you always had a home - that was the thought. As it turned out, the economics of a very small farm in the Central Valley of California caught up with them, and after too many years of deficit-farming, Mom and Dad were forced to file for bankruptcy. They lost the Nagai farm, though in a negotiated settlement with the new owners, made a deal to remain on the piece of property on which the house stood for some 7 years, after which they would have to "move into town." You would never have known that Dad was sorely disappointed his dream died for the desire for security, and in the end what was to give them security in their retirement evaporated in the desert where dreams expire. Did Dad hold resentments for his disappointment? I think so. Did he blame Mom? Not openly…

Presbyterian Hospital/San Francisco: When I was at Cal in grad school, I think in 1962, Dad was diagnosed with polyps on his vocal chords, and an operation was performed to remove them. The operation involved removal of his "voice box," his larynx. He ended up with a hole in his throat, and learned to "speak" again by swallowing air and manipulating the muscles in his throat as he burped the air out to form words. At least, I think that was how it worked. It produced a strange raspy-sounding voice that sometimes frightened little children, including his own grandchildren. For an introvert, and one hampered by his "broken English," yet another disincentive for vocal communications. I visited Dad in the hospital shortly after his operation, and found him more reticent and withdrawn than usual. Being one of few words, his new handicap forced him even deeper within, and I spent a very awkward and uncomfortable visit with him. I asked if there was anything I could do for him, if he needed anything, but he nodded, "No," so I just held his hand throughout my visit. When I left the hospital, I cried.

|

|